Forced displacement remains a critical challenge in East Africa, impacting millions and straining resources across Somalia, Ethiopia, South Sudan, and Uganda. This data story, informed by studies supported by the World Bank-UNHCR Joint Data Center on Forced Displacement, highlights the urgent need for evidence-based policies to foster inclusion and self-reliance among displaced populations. The core problem lies in the current encampment approach and fragmented policies that isolate displaced persons, limit their economic contributions, and hinder access to essential services.

Our main objective is to advocate for a shift towards inclusive, rights-based approaches that enable mobility, access to work, and integration into national systems. The overarching message is that by moving beyond camps, strengthening national services, and leveraging inclusive data, East African nations can transform displacement challenges into opportunities for sustainable development, benefiting both displaced populations and host communities.

Moving Beyond Camps Towards Inclusive Development: Key Policy Recommendations

These policy recommendations stem from different studies and surveys in Somalia, Ethiopia, South Sudan, and Uganda, supported by the World Bank-UNHCR Joint Data Center on Forced Displacement, to inform evidence-based policies and allow better inclusion of displaced populations with the host communities. If successfully implemented, these five recommendations could help transform the challenges of forced displacement into opportunities for inclusive growth and sustainable development.

1. Moving Beyond Camps, Towards Inclusion

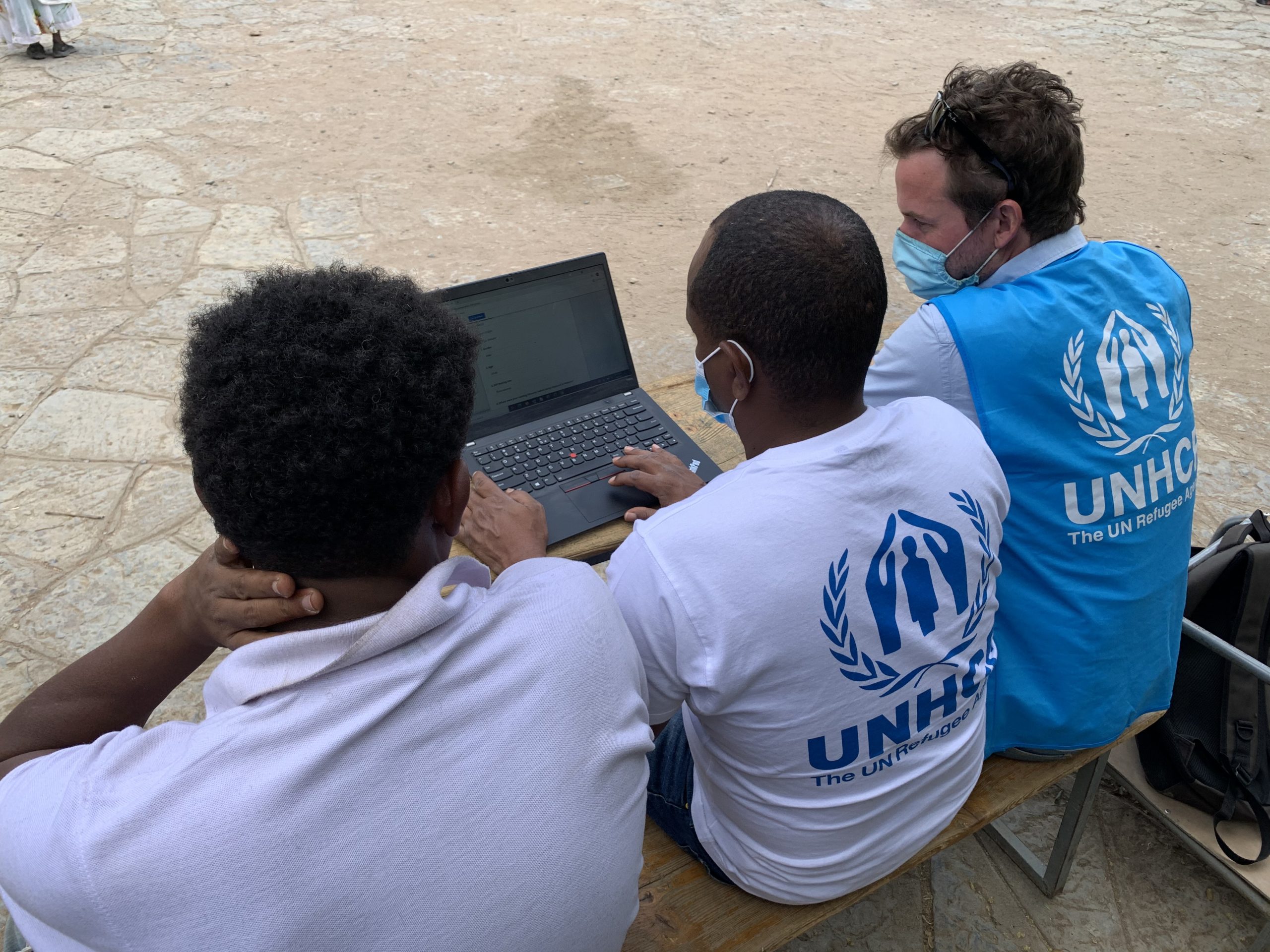

Photo: © UNHCR/Sona Dadi

While temporary shelters and designated camps may offer short-term relief for displaced people, they ultimately leave refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) isolated and limit their potential contributions to the local economy. To foster better inclusion and benefit host communities, it is essential to enable mobility, allowing access to areas with greater economic opportunities.

Tailored housing models — such as private rentals, locally built homes, and low-cost social housing — provide viable alternatives to the encampment approach. This contrasts with the existing reality of refugees, who often live in camps and endure precarious and overcrowded housing conditions. Although incipient, Ethiopia’s policies promoting an out-of-camp approach have shown promising results in improving refugee integration and self-reliance. Expanding and refining such initiatives could serve as a starting point for other countries affected by displacement seeking better alternatives to camps. For example, the Socio-Economic Survey of Refugees in Ethiopia (SESRE) highlights local population support for refugees’ relocation to other parts of the country, endorsing their right to work, education, and healthcare.

Photo: © UNHCR/Tiksa Negeri

2. Enabling Self-Reliance and Access to Work Achieves Dignity and Sustainability

National governments should support people forced to flee by fostering self-reliance and promoting inclusion through eased travel restrictions and improved access to local labor markets. Given the diverse challenges across and within countries, a one-size-fits-all approach rarely works. Instead, authorities can develop local interventions that consider the specific needs and characteristics of displaced persons and host communities.

Despite local variations, certain barriers persist across regions. Limited access to documentation and legal permissions to move and work freely remain a major obstacle for millions of refugees in East Africa. Rather than confining displaced people to enclosed camps, policies should prioritize mobility and the right to work and self-employment, ensuring dignity, economic growth and sustainability. Gender disparities are also a cross-cutting issue. In South Sudan, male refugees participate in the workforce at significantly higher rates than their female counterparts—a gap not observed among host communities. Inclusion policies and interventions should ensure that women are not left behind, enabling all displaced individuals to achieve economic independence.

Photo: © UNHCR/Diana Diaz

3. Overcoming Barriers and Strengthening National Health Services

Displaced persons face significant challenges in accessing healthcare, particularly outside camps, where they encounter multiple barriers to national health services. The right policies can ensure that refugees and internally displaced persons can access national health services through legal documentation, financial support, and expanded public healthcare infrastructure.

While some camps provide free medical care, out-of-camp refugees and internally displaced persons often rely on costly private providers due to restricted access to public healthcare facilities. In Ethiopia, 91% of in-camp refugees surveyed receive treatment when needed, compared to just 71% of out-of-camp refugees, who struggle with affordability and exclusion from national services. In Somalia, fewer than 40% of displaced individuals in need can access medicine or medical care, primarily due to high costs and distance from health facilities. Policies can focus on integrating displaced populations into national health systems and providing financial support to overcome cost barriers.

Photo: © UNHCR/Sarah Jane Velasco

4. Promoting Accessible and Gender-Inclusive Education Policies

Governments can include refugees and internally displaced persons in national education systems, eliminate financial barriers, and invest in gender-inclusive policies. The financial burden of maintaining separate education systems reinforces the case for investing in robust national education frameworks that benefit all children regardless of their displacement status.

Despite its importance for inclusion—particularly for young refugees—education remains out of reach for many due to poverty, logistical challenges, and social barriers. For instance, Uganda’s 2022 survey shows that while 64% of children aged 6-12 were enrolled in primary school, this number drops dramatically for secondary school, with only 7% of boys and 4% of girls aged 13-18 attending secondary school. In Somalia, school fees prevent numerous refugee children from attending school, with girls disproportionately affected. In South Sudan, only one-third of female refugees complete primary school, compared to half of their male peers. In Ethiopia, most refugees receive only primary-level education, severely limiting their future opportunities. Investing in a national approach by expanding educational infrastructure and vocational training programs enhances long-term prospects for both displaced and host communities.

Photo: © UNHCR/Elisabeth Arnsdorf Haslund

5. Bridging Data Gaps with Statistical Inclusion

Governments and international organizations can collaborate to include displaced people in national data collection efforts, ensuring policies are informed by comprehensive and comparable data. Reliable data is crucial for effective policymaking, yet displaced people are often excluded from national surveys. In Somalia, for instance, the displaced population is assessed separately, making it difficult to compare their conditions with those of host communities and devise effective solutions.

However, the Socioeconomic Survey of Refugee and Host Communities in Ethiopia (SESRE) and Uganda’s inclusion of refugees in national surveys mark significant progress. These initiatives provide a more accurate picture of refugee livelihoods and inform targeted policies. Expanding such inclusive data collection frameworks across regions will help bridge statistical gaps, enabling governments and aid organizations to develop more effective, evidence-based interventions.