Displacement and poverty – The consequences of conflict in the Central African Republic

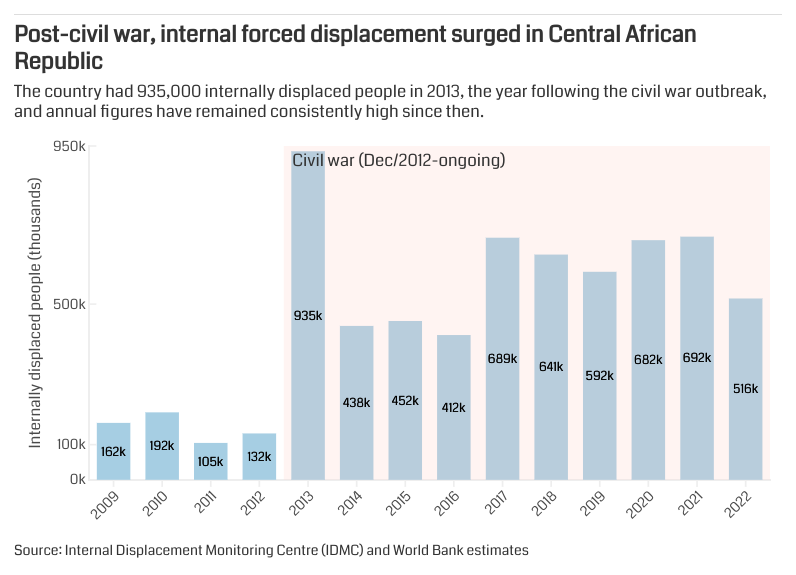

Conflict in the Central African Republic (CAR) has a long history. Although it escalated dramatically in 2012, it has abated since then. But it’s still horrific. People have been driven out of their homes, been maimed, women have been raped and children killed. Some 750,000 Central African refugees have sought safety in other countries and around half a million people remain internally displaced.

Sabine, 45 years old has been living on the site of the Catholic church with her three children for six years since she had to flee from her village. “I can’t feed my children properly. By eating the same things, my children get sick every day. I have a grandson who suffers from anaemia because of the non-vitaminised food,” says Sabine. Chanel Igara/NRC, Central African Republic, July 2022

The level of deprivation that these people face is truly shocking. Sabine (above) has lived in a displacement camp for six years and can only afford to feed her children cassava leaves. Situations like hers and that of other sectors of the population are described in detail in CAR’s first ever poverty assessment “A Roadmap towards Poverty Reduction in the Central African Republic” which was released on November 16.

While CAR ranks at the bottom of the human capital and development indices (188th out of 191 countries in 2022) the situation is worse for internally displaced people (IDPs). The report found that IDPs living in camps are worse off across most poverty metrics which is similar to the situation faced by IDPs in several other countries. A study conducted by Utz Johann Pape and Ambika Sharma in 2019 concluded that IDPs are generally poorer and more vulnerable than host communities, proving that the effect of violence is as devastating as it is enduring.

As poverty is projected to remain high in CAR over the next five years, understanding the socioeconomic dynamics of poverty will allow us to devise solutions to it. While the report stresses the importance of developing human capital, the proximity to services such as health facilities and schools, is a constraint. About 30 percent of primary-school-age children and 55 percent of secondary-school-age children live more than one hour by foot from their nearest primary and secondary school, respectively.

The CAR poverty assessment was launched by the Prime Minister, Félix Moloua, signaling the government’s commitment to addressing poverty. The poverty assessment provides a roadmap for the government, the Bank and other development actors to do this as well as providing solutions to internal displacement and durable solutions for refugees returning to CAR.

The absence of the state services and the rule of law means that people who want to return to home, cannot go back. If we don’t address the causes of forced displacement, it threatens development prospects and poverty reduction.

Yours sincerely,

Aissatou (Aisha) Dicko

Head of the Joint Data Center on Forced Displacement